A “Running” List of Birds in 2018

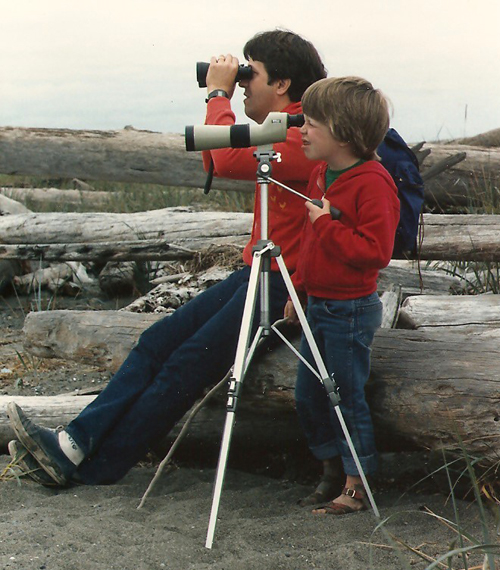

I started birding when I was five years old, about (mumble) years ago. I’ve also been a serious runner for well over a decade, and will continue as long as my knees allow. With these two outdoor pursuits (I hate treadmills), there’s bound to be overlap; I’ve found myself sprinting after the chance to see a rare bird (McKay’s Bunting, 2012) and, due to my long-standing aversion towards headphones, I definitely notice birds while running. The list of species seen while running would be respectable, I’m sure, if I’d ever bothered to write them down.

Nevertheless, I remember a few highlights: Red-necked Phalaropes while doing laps on the lower deck of an Alaskan cruise ship; a Virginia Rail that skirted in front of my feet on a rural road on Vashon Island, Washington; a lifer American Three-toed Woodpecker working a roadside tree stump in deep woods Montana; and a pair of Black Scoters at Discovery Park in Seattle, to name a few. Certainly the most exceptional was a Rustic Bunting that spent a few months wintering with a flock of juncos in San Francisco. As a rarity blown off course from its native Asia, it was well-known in the birding community and conveniently situated along a preferred jogging route only a mile from our apartment at the time.

While I have accumulated a few memories, I don’t have an official tally. It pains me to think about “the list that could’ve been.” Unfortunately, I’d think to myself, too much time has passed.

Then January 1, 2018 happened. I’m not one for New Year’s resolutions but I thought “why not keep track for a year?” This arbitrary date aligns nicely with the starting gun for when birders’ try to find as many species as possible in 365 days, a so-called “Big Year.”

Compared to my brethren who fly to every corner of the U.S. in pursuit of our feathered quarry, my year won’t be “big.” This endeavor is born from curiosity, not competition. I’m just going to keep running three days a week, like normal. I’ll aim for 15 to 20 miles a week following largely urban routes, like normal. Nearly all runs will start from our apartment in Washington D.C., like normal. I will notice birds by sight and sound, like normal. At the end of each run, however, I will take note of what I’ve seen or heard in a Google Sheet.

This endeavor may influence the destination of a few runs, sure, but the emphasis will always be exercise. Being the parent of a young child, spare time is at a premium, and, if given the choice between running and birding, I’ll pick a trim midsection over a plump species list. Rare birds, no matter how exceptional, won’t help me stave off the diabetes.

This way I can reliably pursue both passions—killing two birds with one stone. Or, perhaps, “two runs with one power gel.”

Having never heard of another birder/ runner who’s done this, I sketched out some guidelines:

- No binoculars.

- No driving to special habitats at specific times of year for a light jog just to add a couple species to this ephemeral list.

- If I happen across generous birders with their spotting scopes trained on a new species, I’ll take a look (I wouldn’t want to be rude).

- Birding should not negatively impact my normal distances or pace.

- I will only count wild birds that can be confidently identified by sight or sound.

- I will stop at a few prime locations mid-run to watch and listen; I may even lightly stretch to mask my true intentions.

- I’m not sure where I’ll end up on December 31. I’ll aim for 100 species, but hope for more. Will every bird be recorded? No, many distant silhouettes, quick flyovers and indistinct chip notes will go unidentified.

But that’s birding.

It’s looking good so far: By the end of my second run, I’d already tallied 25 species. Sure, they were on opposite coasts and thus included different sets of easily tallied “common birds.” But still, not bad for freezing temps in January.

My knees held up, too.

Swallow-tailed Gull: An ABA Rarity for the Ages

Chasing rare birds is rarely convenient.

Unless you’re single, unemployed and avoid human interaction, jumping in a car at a moment’s notice to drive likely hours away will definitely impact “real life.” Thus, when a hot sighting hits the wires, hard decisions will need to be made, often amidst incredulous gazes from coworkers or skeptical scowls from a non-birding partner. For those with families, pre-chase rituals also involve bartering with a hopefully patient– if not totally understanding – partner to rebalance responsibilities to compensate for absence: “I’ll pick up dinner on the way home” or “I’ll catch our next child’s high school graduation.” In households with only one pair of binoculars, the birder frequently doesn’t have many chips on their side of the marriage table; likely, most run on house credit.

Personally, I don’t think I was in a deficit. As a recent father and a notoriously heavy sleeper, however, I wasn’t comfortably in the black either. For some birds, though, you gotta take a deep breath, slide all your chips across the table and hope for the best.

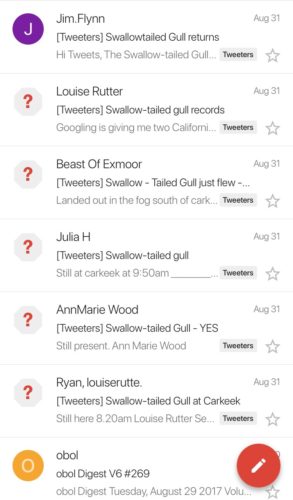

It started as a somewhat stressful afternoon running errands to prepare for our daughter’s first birthday party. She was sleeping so my wife ran into a couple shops while I stayed in the car and faithfully executed my daily ritual of scanning my birding email, which compiles notices from six different states on both coasts. I saw repeated mention of “swallow-tailed” in the truncated email subject lines and I expected a Swallow-tailed Kite, a gorgeous species of hawk from the southeast and a noteworthy sighting in Virginia or Maryland near my current home in Washington D.C.

Wait, these emails are coming from Washington State. I clicked: “Swallow-tailed Gull.”

What? I went back to find the email that started it all: a birding buddy Ryan Merrill found a Swallow-tailed Gull in Carkeek Park near Seattle that morning.

I was shocked. Could it have escaped from captivity? It’s a long distance from its native Galápagos Islands off of South America—3,800 miles, in fact. Plus the species is nocturnal. This wasn’t making any sense.

People were reporting that this was only the third time this species had been reported in the ABA (“American Birding Association” area, i.e. U.S. and Canada), and the first sighting since the early 1980’s.

“What is it?” My wife asked as she saw my face as she approached the car. She was concerned someone had died. I was nearly speechless. “Babe, a really, really rare bird was reported thirty minutes from here.”

I think I actually heard her eyes roll.

I didn’t ask the obvious question for ten full minutes—I was dying inside. “People will be flying from all over the country to see this bird,” hinting at my intention without stating it outright. In a tremendous feat that was equal parts love and acquiescence, she gave me the terms: “Okay, we will go. I’ll give you 45 minutes. If you stay longer, you’ll need to find another ride back.” I eagerly accepted the terms and we headed north. The fact that I was without binoculars didn’t matter.

My wife says my feet hit the pavement of the parking lot at Carkeek Park before the car stopped rolling, but I don’t remember. The first vista overlooking the beach, however, rings clear: I saw a horde of birders facing the same direction towards a flock of gulls. This is critical because, as any bird chaser knows, there’s a high chance a rare bird has moved because, you know … it has wings.

The rest was a bit of a relief-induced blur: I caught up with some former birding friends, two of whom let me borrow their scopes; I enjoyed prolonged studies of the grayish hood, thin eye ring, and distinctively angular bill tip of a Swallow-tailed Gull; and I returned to the car with twenty minutes left on the matrimonial timer.

Check. I haven’t asked but I may even have a few chips left in my stack.

Now, does anyone know if there’s a leaderboard for birders who have successfully chased a Code 5 rarity without optics?

I’m asking for a friend.

Montezuma’s Revenge: A Quail of a Tale

In the Davis Mountains of remote west Texas, I finally overcame a multi-year bout of “Montezuma’s Revenge.” Eight years, in fact. I first succumbed to the ailment in Southeastern Arizona. Three years later, it flared up again on my second trip to the region. While it was most intense in the grassy pinewoods of the Chiricahua Mountains, the ailment percolated deep within my bowels for years—even mere mention of the area would double me over with sharp pains of regret and anguish.

Relating gastrointestinal distress to birdwatching– or, in this case, birdseeking – may seem extreme, but the analogy conveys the urgency (of the search), and the relief of release (when the quarry is finally spotted). In this case, the aptly-named Montezuma Quail.

Since childhood, this species was quarantined in my imagination as an abstract concept based on its impossible beauty and very limited range in the American Southwest, hundreds of miles from my native Seattle. I heard they existed and many people – whom I thought I trusted – conspired to confirm this, but I was incredulous; the striking patterning and coloration of this dove-sized species just didn’t seem possible.

After two, week-long trips to the region, it became clear that this conspiracy was far-reaching, involving even local Arizonans who boldly claimed to regularly see this supposed species.

“Just go up this trail in the morning, I always see them up there,” said one. “Oh yes,” said another. “Drive up this road and you’re almost guaranteed to see one.”

After numerous pre-dawn mornings scouring the side of the road at seven miles an hour, I called “quail shit” on my Arizonan hosts. I returned to Seattle with my mind full of beautiful species – Elegant Trogon, Grace’s Warbler, and Violet-capped Hummingbird, to name a few – but they were all overshadowed with what could have been. Again.

Six years later, I signed up to co-lead a trip to west Texas with Victor Emmanuel Nature Tours and BirdNote. The itinerary listed Montezuma Quail as a possibility, stating that the Davis Mountains was one of the best places to see this “furtive species.” My skepticism piqued; it only confirmed for me how far and wide the conspiracy had spread.

Over a dozen people signed up for the trip. Perhaps, collectively, the group had enough karma for the Birding Gods to shine favorably upon us and grace us with even fleeting glimpses of one of its most cherished disciples. Or, most likely, I would lead the group – who had paid good money for this experience – down into the brush-lined pit of despair that had defined my experiences in Arizona.

I compiled a mental list of possible life species on the trip and, as one day led to the next, I was tallying checkmarks with incredible views of southern specialties like Varied Bunting, Gray Vireo and Colima Warbler. I almost mentally suppressed the sixth and final “possibility” – the Montezuma Quail. I was reticent to set myself up for yet another failure.

The other co-leader, Bob Sundstrom, caught glimpse of a pair of quail early in the trip while on a bathroom break away from the group. After combing the brushy hillside like a CSI tech, I confirmed that the two birds likely shape-shifted into a sand-colored stone, or a stone-colored bush.

It would be several days until we visited the Davis Mountains – the magical land where these feathered unicorns roam free – on the last stop of the trip. Our best shot was our only shot. After dropping the trip participants off at the historic Hotel Limpia to attend to a surplus of wine, Bob and I set out to scout locations for the following morning. This wasn’t birding altruism: It doubled my chances to achieve gastro-avian relief.

In the big white van, we worked up and down the two roads at the Davis Mountain State Park, finding the reported nest cavity for the Elf Owl – North America’s smallest owl species – above the dry riverbed but (surprise surprise) striking out at Camp 62 where Montezuma Quail had been reported just 24 hours prior. It was across from the trailhead to “Montezuma Quail Trail,” further twisting the dagger of irony.

We drove west into the mountains towards the Davis Observatory. I stared at the passing oak woodlands and lion-hair grasslands interspersed with ranches and wondered how many years I would have to wait before I could finally lay eyes on this friggin’ bir—

“MONTEZUMA QUAIL!” Bob screamed from the passenger seat, pointing to a grassy roadside passing at 55MPH. We turned around and crept at a quail’s pace along the highway, my eyes frantically moving between the gravel shoulder and the rearview mirror: I didn’t want death to be delivered at the grill of a Mack truck. At least not before I saw this stupid bird.

Then they appeared.

I was speechless. Two young males quietly and confidently foraged for gravel, seemingly oblivious to our approaching steel behemoth. Even though the pair lacked the male’s saturated wine-red plumage set against speckled black and white, the intricacy of their plumage was mesmerizing.

We enjoyed them for a few minutes – about as long as we were comfortable parking on a highway – before we dutifully returned to the hotel to round up our convivial participants to show off our quarry. All for not: Twenty minutes later, the birds were gone.

I searched with renewed energy the following morning. Our first stop at the state park yielded nothing; a walk at the nearby McDonald Observatory afforded an impressive flock of migrating songbirds but, again, no quail. Down the road, a mile-long walk through Lawrence Wood picnic area gave us beautiful views at the long-sought Black-chinned Sparrow – our first from the trip. Stepping off trail on the walk back flushed a small flock of quail. As quickly as they exploded out of the grass – and shot up our heart rates – they disappeared into the rocks of a nearby hillside. Glimpses were afforded to a handful of trip participants; a few more heard the ominous call of the male, a sound like the ascending, metal-on-metal trill of a train inching to a stop.

Unfortunately, that was it. That was our last shot. We solemnly got back into the van, happy with the sparrow, but always thinking about what could have been. One of the biggest birders on the trip was going back home with only 7 of the eight targets she had for the trip. Ironically, she was from Arizona.

I knew the feeling well.

I drove the remaining stretch of rural highway out of the Davis Mountains towards El Paso. We recounted the best sightings of the trip while I scanned the side of the road. The jovial chatter in our van was a good sign—the satisfaction was palpable. Bob, sitting in the passenger seat, removed his glasses to clean them in his lap.

A softball-sized pair of rocks protruded from the horizon of the road as we crested a small hill. One moved.

“Montezuma Quail!” I yelled, slamming the brakes to a near four-wheel skid. We maneuvered the three-vehicle caravan around – stressing an already overworked drivetrain – and crept slowly onto the opposite side of the road. Nonchalantly, our quarry continued to forage as exaltations of relief passed through the van, noses pressed against the glass.

For fifteen minutes we sat, engines idling, stunned. The male’s striking black-and-white head juxtaposed against an intricate collage of reds and browns, like a small, portly man wearing a Mexican wrestling mask and a camouflaged cloak. The female, though more drab, was also impressive, like a sun-faded version of her male counterpart. The pair gradually retreated from the road. Interestingly, they didn’t run with their heads upright – like other quail species – opting to lower their heads to snake through nearly unseen tunnels in the grass. Stripes running along their back from head to tail obfuscated their exact location, reminiscent of the optical illusion that makes it difficult to spot a retreating garter snake.

We pulled away, turned around, and continued down the road towards El Paso sharing high-fives and photos. The Birding Gods shone down, providing a brilliant ray of light as the trip was fading to dark.

I had my revenge, and it never tasted so sweet.

Never satisfied, I was already pondering the next gaps in my life list. How about a Red-faced Warbler or Manx Shearwater?

A Tour of the Lion Statues of Washington D.C.

Travel Notes: Chile and Argentina

Travelers know the questions one must field after returning from a trip. “How was the weather?” “What was your favorite part?” “How was the food?” all hurled at you by coworkers as you hug the office coffee maker, trying to fight off jet lag. For some, there is genuine interest in your trip. For most, it’s a perfunctory exchange where, once you start responding, their eyes glaze faster than a Bavarian strudel.

Except me. Excuse my bleary-eyed Monday-morning brethren, I want to hear all about your trip. Got pictures? Even better. Go ahead and swipe through all those sandy beaches, ancient ruins and decadent meals. With a limited budget and perennially maxed-out vacation time, it’s a vicarious escape for me, an opportunity to daydream between emails and spreadsheets. I celebrate the fact that my dream destination list, no matter how much I travel, never shortens.

My wife’s grandmother is a similar traveler. Last year, despite being well into her 80’s, she took trips to Mexico and Vietnam. And based on the handsome selection of photo albums on her bookshelf, this isn’t a recent urge.

One Thanksgiving, I flipped through one of those albums. It was from a trip she took to Nepal and Tibet in the late 1990’s with her now-deceased husband. As a digital-native amateur photographer, I admired the images for the deliberateness implicit in single-exposure film and the warm texture that dances somewhere between the Sierra and Valencia filters on Instagram.

But the most lasting impression was left by a single, hand-typed page in the back of the album. It was a simple list of memories – one or two sentences in length each – that served as an addendum to the visual accounts preceding it. Each entry was brief and evocative, capturing a piece of cultural detritus one collects while crossing borders. An analog tweet from an offline status update.

I used to take copious notes while traveling. In college, I studied abroad in Asia and dedicated an hour every evening to journaling that day’s events, no matter how mundane. Even though none of these journals have since been cracked, I know they’ll dutifully hold all the memories that would otherwise be lost to time.

I don’t know why I stopped journaling. It’s partly because “and then we did this, and then we did this, and then we did this…” doesn’t lead to elegant prose, a goal that most readers should recognize as already unattainable. I also discovered that foreign cultures have beer.

Not matter the reason, this type-written page inspired me. Certainly I could manage a few sentences scribbled in the Notes app on my iPhone, or in the Rite-in-the-Rain pad of paper I always carry in my back pocket?

A two-week trip to Chile, Argentina and Uruguay seemed like a good opportunity to give it a shot.

CHILE

Santiago is a crown of sleek skyscrapers amid a cushion of snow-capped mountain tops, reaching staggering heights.

Everyone has a mountain bike in Santiago; there are very few road bikes.

On Sunday afternoon, the road to top of San Cristobal is packed with walkers, runners and cyclists.

Casinos are illegal inside Santiago.

Pisco Sour (mixed with a potato-derived alcohol similar to vodko) or Piscola (same alcohol, but with Coke) are the drinks of choice.

Meals are meat, meat, meat, and fish. Repeat every day for lunch and dinner.

Stray dogs are numerous, tame and remarkably healthy. Many have “night homes” with Santiago residents and roam the street during the day. One chow mix leaned his head against my leg within blocks of our hotels on our first morning then followed our group as we walked a local park looking for birds. He was a welcome addition to the group until he chased through a flock of lapwings and thrushes, returning triumphantly to our group as if to say “hey guys, did you see that?”

European-style eating abounds in Chile with dinners starting around 9pm. Mid-afternoon snacks are their bread and butter. Literally, bread and butter.

There’s no “Chilean” look: a few are descendants of the native Mapuche while many are clearly of European ancestry.

It looks like many private homes in Santiago are the love children of American architects and the post-modern orgasm of the 1970’s.

Wooden funiculars – antique, rickety, and incredibly charming hybrids between gondolas and escalators, with twice the legal liability of both combined – are widely used in the hilly, coastal city of Valparaiso.

Coffee was only introduced to Chile – or at least it became popular – a few years ago. Coffee is mostly imported from abroad despite the fact that South America produces so many beans.

Passengers applaud in a synchronized rhythm when the plane lands, no matter how uneventful the flight. I can respect a culture that appreciates the miracle of flight.

ARGENTINA

There’s an edge to the people and transactions here that you don’t find in Chile, and it’s not necessarily a pleasant change.

“Crossing like cows” is how our guide described the way in which people blindly cross intersections here, empowered by laws in extreme favor of pedestrians. Our tour bus nearly removed several people from the Buenos Aires gene pool.

During hailstorms, motorists will immediately park under trees to avoid damage from the falling ice chunks, which is not covered by insurance. Most cars just stopped in the middle of the arterial, while others drove up and over curbs and over lawns to find cover in a street-side park.

Everyone carries a leather satchel that includes a small gourd, slightly bent silver straw with filter, a hot water thermos and a large container of maté, a type of tea. Some may picture a small, dainty, neatly-contained teabag; a heaping handful of grass clippings is a better visual comparison. Some Argentinians garnish with lemon, most drink it raw. Piles of spent maté are frequently encountered and resemble the droppings of a well-hydrated herbivore.

Short, quick sentences jotted throughout the day was a very manageable way to journal while traveling. Capturing memories while being able to imbibe during the evenings? That’s a win.

In other news, as predicted, my travel wish list grew: now I need to see Bolivia and the pampas of Brazil.

Cold-blooded Volkswagens: Seeking Leatherback Turtles in Trinidad

Travel Notes: Trinidad and Tobago

This is a regular series where I go to the farthest reaches of the globe, walk around, observe daily life, eat some food, maybe take some photos, and say “wow, that shit would not fly back home.”

It sounds elitist and dismissive, but it’s quite the opposite. If I haven’t expressed some sort of disbelief with what I have experienced while traveling, I simply haven’t explored deeply enough. This is why I keep reaching for my passport and, this time, it was to go to Trinidad and Tobago.

It was my second time to a Caribbean island in less than a year. I saw some great birds but I also experienced another beautiful country. I wasn’t disappointed.

English is the Official Spoken Language, Kind Of

Trinidad is a former British colony and thus, English is the official language and nearly everyone in the tourism industry speaks it flawlessly. Go off the beaten path or listen when your hosts speak to one another, however, and it’ll become clear that what you hear is a slowed down and tidied up version of their own English-based Creole. In a linguistic system one part efficient and two parts indifferent, Creole strips its predecessor of many elements our ears have grown to appreciate, like “s” sounds and the breathy pauses between words. Numerous times I found myself concentrating intently on peoples’ mouths in an uncomfortable space where I both recognized my own language yet had no grasp on what was being communicated. And squinting harder didn’t help. Any glimmer of recognizable English was quickly dashed by a perplexing juggernaut of consonants and vowels. Even the phrases I understood were used in unfamiliar contexts: “Good Night” is an evening greeting in Trinidad, not the intimate farewell one says just before going to sleep. The pace of the language thankfully is formed by the tropical climate; phrases mellifluously follow one another off the tongue like a slowly poured rum punch. It was fun to drink in.

Rental Car Switcharoo

I booked a car on Travelocity through “Fox Rental Car” for our arrival in Trinidad. When we landed – at around 9pm after a full day of travel – we couldn’t find the Fox Rental Car kiosk. Avis, Alamo, Budget, and Thrifty were all present; Fox was nowhere to be seen. Even the tourist information center was closed. Thankfully, the gentleman at the cab stand agreed to use his personal phone to call the number on our email reservation. An enthusiastic voice on the other line said that he’d be there within 20 minutes. Nearly an hour later, a young man clad in blue jeans, a black shirt and flip-flops showed up with a laptop case and clipboard—none of it branded “Fox.” I passed a glance at the paperwork and noticed a different name entirely: “Xtra Car Lease.” The logo looked to be a product of Microsoft Clipart to my incredulous eyes. After some cautious prodding—but before he ran my credit card on his portable reader—we learned that Fox contracts with his company to provide cars in countries where they don’t have offices. Most Americans would be unsettled by this lack of transparency, but my need for a pillow overruled my skepticism. We swiped my credit card, checked for damage, shook hands and took off for the mountains in our dramatically underpowered Nissan.

Zip-tied Hubcaps

Let me be perfectly clear: there aren’t many problems in life that can’t be solved with duct tape, zip-ties, SuperGlue or a combination of all three. I had just never seen Zip-Ties used so blatantly on a car. Personally, I appreciate the ingenuity of using plastic fasteners to keep the hub caps attached to the vehicle. Americans, who aren’t used to driving on the other side of the road, may be unwittingly prone to clip curbs, thus liberating the car of any disk-shaped pieces of plastic located at the point of contact (ask my dad about Australia in 1998). It does, however, raise concerns about how issues with other, perhaps more important, parts of the car were fixed. For me, it was a nice accent piece. And damned if we didn’t return the car with all four hubcaps still attached.

“When will we know if the 4:25 flight is delayed?”

After spending two beautiful days exploring Tobago, Trinidad’s accompanying island to the north, we arrived back at the capital city, Scarlborough, for our return flight. The airport is small but there are flights between the two islands every thirty minutes. We were informed upon our arrival that our flight, which left in about an hour and a half, would likely be delayed. Apparently a mechanical issue earlier in the day had had a cascading effect on all scheduled flights. But the Caribbean Airlines employee suggested that we stay nearby because they may be back on track by the time our flight was scheduled.

One look to the flight status board stated that the 4:25 flight was on time, so we went across the street to seek much-needed air-conditioning in the airport café. Flight updates were projected over the café’s loudspeaker, but if there’s anything that can make English-based creole less intelligible to American ears, it’s amplifying it through a speaker beaten down by time, salty air and humidity.

At about 3:50, less than thirty minutes before our flight was to take off, I left the cool confines of the café to check the flight status: “ON TIME.”

To verify, I waited in the growing queue to speak to a representative.

“Excuse me, is the 4:25pm flight still delayed?”

“We don’t know yet.”

“OK, when will you know?”

“4:26.”

I scanned her face, waiting for a hint of humor. No, she was serious: the flight won’t officially be delayed until after it was scheduled to take off. I thanked Captain Obvious and walked back to the café.

In the end, our twenty-minute flight was delayed over two hours. We were late again to pick up our rental car from Xtra Car Lease.

Dangling Power Lines

Even if these were well insulated as to not cause any harm from electrocution, there are very few instances where one has to navigate around powerlines during a normal day. If you do, you have bigger issues to worry about.

Road Conditions, No Bull

There are some beautiful windy mountain roads on both Trinidad and Tobago: lush foliage, isolated streams and impressive vistas. Due to the conditions of the road, however, the passenger was the only one who could enjoy them. Massive potholes, large piles of gravel, stopped cars, and veering oncoming traffic—all in a country with the lowest “warning sign to blind corner” ratio I’ve ever encountered—meant that the driver couldn’t ever take their eyes off the road. And sometimes the eyes of both the driver and passenger are affixed on the road, specifically on the massive bull in the compact pick-up truck ahead of them.

The “No Wave”

Most who know me know that I am fairly even-tempered. But one thing that gets me really fired up is when drivers do not wave when you obviously took precious time out of your day to let them pass. Clearly, the ten seconds it takes me to back up my car is worth the 0.000015 calories required for you to lift your finger off the steering wheel to show your appreciation. Interestingly, Trinidadians do not wave to one another while driving, or at least not to us. Perhaps it’s a national referendum to save energy considering the number of blind corners and narrow passages exist in this country; drivers’ hands would spend too much time away from the wheel.

“Chicken Lane”

Just outside of Trinidad’s capital, Port of Spain, we encountered a five-lane road where the center lane was dedicated to whomever was using it. It didn’t matter which direction you were going: if you were there, it was yours. It wasn’t a turn lane. People were driving down at the same speed of traffic, and the direction of cars on this lane changed from block to block.

Customer Service

It could be us, but we never really encountered any “service with a smile” while in Trinidad and Tobago. We certainly don’t have high expectations and while I’m “lactose unpleasant” and Toby has a wheat allergy, we are generally low maintenance and affable. We certainly never found any bubbly personalities in the service sector. Transactions were helpful but very, um… transactional. While it was approaching closing time, Toby’s request for a piña colada at a restaurant was met with an overt eye-roll from our waitress as she walked away, to the extent where we didn’t actually know if she’d return with the drink (she did, it was delicious). She wasn’t exactly overjoyed with my request for a double rum, neat; a drink, need I remind you, that is the simplest to prepare (tilt bottle over glass) and offers the highest profit margin of anything in the restaurant. It was a challenge for us to break our waiters and waitresses with our charm and wit, and it was one we accepted with aplomb. As for our piña colada waitress, we had to wait until the following day to break her. She was way on the other side of the street but we would’ve see that precious smile a mile away.

But as long as the interaction – no matter how warm or cold – results with a rum drink in my hand, I won’t complain.

Trading Juncos for Jacobins: Birdathon Goes South in 2015

“Oh, you’re trying to find as many species as possible today?”

I was a bit stupefied when these words came out of the mouth of our Trinidadian guide. It was early afternoon, a full eight hours into our Birdathon, and it appeared that the foundational strategy for the 24-hour challenge hadn’t yet sunk in.

Toby Ross, close friend, nature lover and Seattle Audubon employee, and I were just beginning our week-long vacation in Trinidad and Tobago at the renowned Asa Wright Lodge, perched on top a verdant mountain valley on the tropical island of Trinidad. Birdwatchers travel here from around the world to see colorful species from North America and the Caribbean mix with denizens from South America, located just ten miles off the countries southern coast.

As a habitat, the tropical rainforest is infamous for straining the necks of birdwatchers who seek fleeting glimpses of parrots, toucans and cotingas high in the dense canopy above. At Asa Wright, you can sit comfortably—coffee in hand—from the lodge’s well-situated veranda and effortlessly spot birds on treetops down valley, all while dozens of species of colorful hummingbirds and tanagers visit feeders almost directly in front of your face.

As Toby and I planned a full-day effort in an environment replete with unfamiliar species and sounds, we knew that local knowledge was necessary to find as many species as possible. But when birding is so easy, and in a region already renowned for a unhurried approach to life, it was hard to instill the urgency required for a “Big Day.” Our requests for private guides at the front desk were met with counteroffers to sign up for established tours. Questions to the on-staff naturalists about which habitats would offer the longest species list were met with shrugs and slightly bewildered expressions.

It was pretty clear that Birdathon this year was going to be different.

Truth be known, it wasn’t difficult to adopt an approach more agreeable to our Caribbean hosts. Compared to previous Birdathons, my normally long drives to prime birding areas were replaced with a short, sleepy shuffle to the famous verandah. And when I first raised my binoculars to my eyes, my usual “first birds” – Dark-eyed Junco, American Robin, House Finch – were replaced with Spectacled Thrush, Crested Oropendola and Orange-winged Parrot.

We were indeed a long way from home.

The excitement continued; another forty species – and a cup of coffee – followed those first three before we sat down to a quickly consumed breakfast. (In order of appearance).

Tufted Coquette

Spectacled Thrush

Crested Oropendola

Orange-winged Parrot

Barred Antshrike

Silver-billed Tanager

Great Kiskadee

Palm Tanager

Cocoa Thrush

Wattled Bellbird

Banaquit

Green Honeycreeper

Violaceous Euphonia

White-banded Tanager

White-necked Jacobin

Gray-fronted Dove

White-chested Emerald

Tufted Coquette

Blue-throated Mango

Yellow Oriole

Golden-olive Woodpecker

Blue Dacnis

Ferruginous Pygmy-Owl

Bay-headed Tanager

Blue-chinned Sapphire

Scaled Pigeon

Long-billed Starthroat

Squirrel Cuckoo

Common Black Hawk

Black Vulture

Tropical Mockingbird

Coppery-rumped Hummingbird

Double-toothed Kite

Shiny Cowbird

Purple Honeycreeper

House Wren

Red-legged Honeycreeper

Rufous-breasted Hermit

Black-tailed Tityra

White Hawk

Piratic Flycatcher

Turkey Vulture

After stuffing fried eggs in our faces, it was time for our 8:30 tour to the famous protected caves which hold a breeding population of oilbirds. This species, which is in its own family, is the only nocturnal, fruit-eating bird in the world. Oilbirds have the face of an owl, the flutter-like flight of a swallow, but the wingspan of a harrier. They howl, growl and click to echolocate in the dark…and this is one of the best places in the world to see them. We were not going to see a lot of species on this field trip, but our target was obviously special.

Streaked Xenops

Oilbird

Golden-headed Manakin

Euler’s Flycatcher

White-chinned Thrush

Trinidad Motmot

Green Hermit

White-bearded Manakin

We were back at the lodge by 10:30 to meet Mahese (mah-HEESE), our private guide for the remainder of the day. We dutifully explained that we wanted to see as many species as possible. He expressed surprise when we confirmed this strategy several hours later. That being said, he was a wealth of local knowledge. I casually mentioned that it’d be fun to see a Pearl Kite, a small falcon a little larger than a robin. “Oh yeah?” he replied. Within minutes, we were on the side of the road with a scope trained on a thick tangle of branches a top a tree: the head of a Pearl Kite peered back from it’s nest.

We were at the entrance to the Arima Agricultural Station, a grassy area known for its birds and the hybrid water buffalo / brahma cows that are bred there. Highlights were a pair of a small flock of Green-rumped Parrotlets and a pair of roosting Tropical Screech-Owls.

Southern Rough-winged Swallow

Rock Dove

Pearl Kite

Tropical Kingbird

Carib Grackle

Ruddy Ground-Dove

Red-breasted Blackbird

Southern Lapwing

Grassland Yellow-Finch

Wattled Jacana

Savanna Hawk

Yellow-chinned Spinetail

White-headed Marsh-Tyrant

Pied Marsh-Tyrant

Gray-breasted Martin

Cattle Egret

White-winged Swallow

Green-rumped Parrotlet

Tropical Screech-Owl

Blue-gray Tanager

Back on the road again, we hit the east coast of the island around 1:00pm. We stopped for lunch at a beach smothered with sargassum seaweed. It was unprecedented on both Trinidad and Tobago and the talk of the whole island. Judging by the smell in the hot midday sun, I could see why Trinidadians were upset. Strategic stops in the mangrove forests nearby afforded us fleeting glimpses of two species of kingfisher; Mahese used a tape to bring in a stunning Black-crowned Antshrike.

Plumbeous Kite

Smooth-billed Ani

Pale-vented Pigeon

Yellow-headed Caracara

Magnificent Frigatebird

Black-crowned Antshrike

Blue-black Grassquit

Ringed Kingfisher

Green Kingfisher

We drove slowly through the temporal wetlands at Nariva Swamp, which were now, unfortunately, dry. We waited at the far end of the swamp, near a stand of palm trees that usually host Red-bellied Macaws towards the end of the day. It was another decision that flies in the face of a normal “big day,” but this charismatic species was worth it. After about an hour of waiting (with rum punch in hand), a pair finally showed up and alit right on the exact palm tree that Mahese predicted.

Yellow-breasted Flycatcher

Rufous-browed Peppershrike

Striated Heron

Great Egret

Gray Kingbird

Yellow-bellied Elaenia

Limpkin

Crested Caracara

Green-throated Mango

Osprey

Yellow-hooded Blackbird

Purple Gallinule

Striped Cuckoo

Giant Cowbird

Long-winged Harrier

Short-tailed Swift

Fork-tailed Palm-Swift

Red-bellied Macaw

It was just an hour before nightfall and we were four species short of 100, our goal for the day. A large Linneated Woodpecker flew over the van as we held vigil for the macaws. As we drove out, Mahese pointed out White-tipped Dove and Yellow-crowned Parrot. Ninety-nine.

“I know where you can get one more,” Mahese confided wryly as we took a left out of the swamp. Within fifteen minutes we were on the side of the road in a small village, looking up at a tree: Yellow-rumped Cacique.

One hundred.

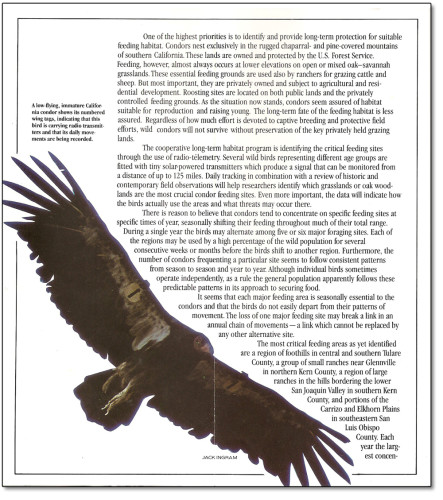

Flight of the (California) Condors

When I was a child, the California Condor made me cry.

Not due to physical trauma, mind you. I wouldn’t have stood a chance against a bird that stood nearly as tall as my five-year-old self.

It reflected emotional pain. I loved birds and, when I learned the plight of the near-extinct species, I was heartbroken. The fact of losing a once-widespread icon of the western frontier was probably lost on me. It had a nine-foot wingspan – one of the largest of terrestrial birds worldwide – and I selfishly wanted to see one in the wild.

I was at a National Audubon Society conference with my mom who then worked at the Seattle chapter. The setting was magical: Asilomar on the California Coast near Monterey. A convivial flock of Acorn Woodpeckers on the premises is what attracted me to birdwatching: my “gateway bird,” so to speak.

Passionate bird conservationists gathered from around the country and, amongst the meetings and networking events, the California Condor took center stage. For the children, educators rolled out an impressive piece of cloth that was cut to represent the life-sized silhouette of the massive bird. Scientists gave presentations that outlined the plight of the species. At that time, in the mid-1980’s, there were only 22 birds left in the wild: the situation was dire. Habitat loss, the pesticide DDT, electrocution from power lines, pressures from cattle ranching and poisoning from lead shot proved too much for the dedicated scavenger.

I cried all night. According to my mother, I was inconsolable.

Word of my concern spread and, by the following morning, the world’s experts on California Condors had assembled at our breakfast table; PhD ornithologists had gathered to assuage the concerns of a five-year-old child. My mother recollects that I didn’t say a word, I just held my chin barely above the edge of the table. Undeterred by my melancholic state, the scientists reassured me that they were doing absolutely everything they could to save the emblematic species.

Unfortunately, I never did see a California Condor in the wild: the last one – a stubborn male called “AC9” – was dramatically caught by scientists in 1987 in a last ditch effort to rebuild the population through an ambitious captive breeding program. All of the California Condors in the world were contained in a facility at the San Diego Wild Animal Park and the Los Angeles Zoo (and later, facilities in Oregon and Idaho). Exposure to humans was strictly controlled: the locations were closed to the public and chicks were hand-reared with life-like condor sock puppets.

It worked. Fast forward thirty years and over 200 condors now form wild populations throughout central and southern California, northern Arizona, and Baja California (with another 200 birds in captivity). In 2003, chicks fledged in the wild for the first time in over two decades (over 40 birds have fledged in the wild through 2014, source).

When my wife and I discussed moving away from our native Seattle, we considered both San Francisco and New York City. As a birder, I mentally calculated that I could see more new species in the Northeast; San Francisco and Seattle are both on the west coast and, as a result, share many of the same birds. But California has condors; Washington and New York do not.

When we ended up moving to the Bay Area (a decision made totally independent of my birding life list) it started to look like I’d finally see a condor in the wild. And, for my 36th birthday, my wife suggested that we give it a shot; Highway 101 along the coastline of Big Sur National Park – a decent spot for spotting soaring condors – was only a 3.5 hour drive south.

The timing of our attempt, the Saturday after my birthday, was significant because it was also the birthday of my non-birding wife. She generously chose to spend the day searching for an obscure bird I’d revered since childhood.

Thankfully, the Big Sur coastline is some of the most beautiful landscape in the world. Mature redwood forests tucked into valleys flanked by curvaceous ridges of verdant pastures, all giving way to a undulating rocky coastline that creates endless points and bays in both directions. We stopped many times to scope the water: within minutes we saw the spout of a gray whale. Then another. And another. Soon, we watched a pod of hundreds of Common Dolphins gradually move north in the brilliant morning light.

At every stop, we found more cetaceans, mostly Gray Whales (migrating north from their breeding waters in Baja), pods of Pacific White-sided Dolphins, and a single Humpback Whale. Kristi used the spotting scope to watch the water while I scanned the ridge lines for soaring raptors. Nothing but Red-tailed Hawks, Common Ravens, and Turkey Vultures so far.

Our most productive spot was a nondescript pullout nicknamed “Sea Lion Lookout.” A group of four feeding Gray Whales allowed for sustained scope views, much to the delight of the many people who stopped to see what we were looking at. This was a good spot for condors so, as everyone looked out, I looked up, waiting for the silhouette that never showed.

We had plenty of coastline left so we continued to the popular Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park. It was a madhouse. Parked cars were overflowing onto the busy highway, so we decided to skip seeing the famous waterfall that everyone was there to see. As Kristi used the facilities before we returned to our car, I looked up yet again. After seeing nothing but hawks, vultures, and ravens, their massive wingspan was unmistakable, even to the naked eye. I scurried to get my binoculars to my eyes: the patches of white feathers extending down the inside of their wing was diagnostic.

California Condors.

As people and cars nonchalantly passed, I set up my scope and enjoyed prolonged views of four condors soaring along the ridge: one adult, with a bright orange head set against a crisp black and white underwing, and three darker, drabber juveniles. Kristi came out long enough for a brief look and a kiss on the cheek—a tradition whenever I see a new species.

Despite the fact that these birds were likely hatched in captivity and released into the wild (you can look up their birth date if you get a good enough view of the color and number of the wing tags, which I didn’t) they were riding wild thermals like they did centuries ago. The birdwatching purist in me appreciated the fact that the status of condors was recently reinstated as “countable” by the American Birding Association, the grand arbiter of what species are established in North America. This validated today’s sighting amongst my birdwatching peers. But that didn’t matter to the five-year-old who saw the wingspan unfurled in front of him three decades ago: he was thrilled.

“Whoa, what’s that!” Kristi broke my daydream a little further down the highway.

Another eight condors were soaring above the ridge line, this time much closer to the road. We quickly pulled off and I watched them for fifteen minutes before they all disappeared. We were in the right place and precisely the right time. It was a fleeting moment, but it’ll stay with me forever.

I wish I could thank the scientists who made it possible to see twelve California Condors in a single day. Over breakfast, of course.