Nemesis bird.

Some may think this refers to the antagonist in a Finnish smart phone game about “ill-tempered” avians. But it’s a term (painfully) familiar to most birders.

A nemesis bird is a title bestowed onto a species of bird after the nth attempt see it (the minimum value for n is influenced by the amount of travel involved, but “3” for cross-country trips and “10” for species found in one’s state are, in my opinion, reasonable values). The bird becomes a glaring hole in that birder’s life list; a painful reminder of all the money and hours spent on numerous failed attempts, usually in driving rain or freezing winds. The name becomes a pejorative mumbled into half-empty pints after a day of birding.

Every birder has at least one or two. And I’ve had a few.

Slaty-backed Gull was one. Every winter, at least one of these rare Siberian visitors is usually reported near my native Seattle. Over the years, I have spent hours sifting through flocks of hundreds of gulls looking for a slightly darker shade of gray, usually matching the brooding Pacific Northwest sky above. The “cold stare” of the Slaty-backed – created by the pale eye set deep in a darkly streaked crown – mimicked the cold winds I often endured searching for that stupid bird. Unfortunately, the locations were far from idyllic: the base of an airport in Renton or Commencement Bay in nearby Tacoma, an industrial area permeated by the pungent smell of a paper mill (hence the derogatory “Tacoma Aroma”).

But, thanks to a local birder, I finally saw that bird earlier this year after, likely, my fifteenth attempt. It was unceremoniously perched on the top of a warehouse. The views were excellent, and the fact that it was no longer a nemesis bird blinded me from the fact that I was firmly seated within the cement-fortified armpit of Puget Sound.

With one nemesis down, I felt like I was on the verge of a hot streak (said every gambler, ever). I confidently scanned for the next glaring hole in my life list: an alpine chicken called a White-tailed Ptarmigan.

I should’ve seen a ptarmigan by now. My wife and I both love to hike and we usually spend three or four weekends every summer on overnight backpacking trips throughout Washington State. Most of our trips are to higher elevations in the Cascade Mountains—prime ptarmigan territory. Whenever we found the appropriate habitat – the confluence of talus slopes, alpine meadows, and snow banks – my hiking partners would often find me scanning the fields of rocks with my binoculars, waiting for one of those rocks to move.

They never did.

I’d even made a couple “ptarmigan-specific” trips to the Sunrise-area on Mount Rainier. One day I hiked a total of 14 miles back and forth on trails where they’d been reported just days prior. It was an ill-informed strategy executed by a man driven by desperation. More patient observers find the right habitat then sit down and wait: the ptarmigan will emerge once you’re deemed worthy.

And, to add insult to injury, it’s a species that’s famous for being dog-tame, even walking through the legs of appreciative observers.

Earlier this summer, my wife and I joined another couple for a hike up to Tuck and Robin Lakes near Roslyn – about 45 minutes east of Seattle. It was a beast of a slog for our first “over-nighter” of the year: 16 miles round trip and 4,000 feet of elevation.

Our camp was in rocky alpine habitat that seemed good for ptarmigan. After an evening enjoying the Super Moon, I spent the morning scouring the area for any signs of bird life, finding only American Pipits and Clark’s Nutcrackers. No ptarmigan. As we ate breakfast before our descent, a member of our party brought me a feather she’d found nearby. Damned if it didn’t look like it had fallen from a ptarmigan.

Ptarmigan 15 – Pasty Birder 0

The following weekend, the same couple wanted to go backpacking again. They had received backcountry permits to coveted Hidden Lake in the North Cascades. Looking down the barrel of another 4,000 foot climb, my wife and I opted to follow another couple on an easier route closer to Seattle. We had Silver Lake near Granite Falls all to ourselves.

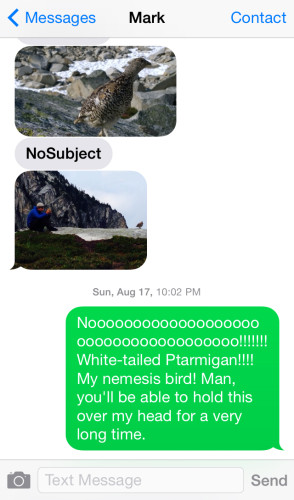

Ding-ding

As we entered cell range on our drive back Sunday night, I received a text from the couple who we almost joined on their hike to Hidden Lake. It included a beautiful image of … yup, you guessed it: a ptarmigan. I wanted to throw my phone through the windshield.

But then I realized the brilliance of my friend’s ways—he had simply downloaded an image online and sent it to me. Smart. I was actually surprised he could spell it correctly and new which of the three species is the only one found in Washington.

Ding-ding

A picture of him with a ptarmigan. No more than six feet away. Son of a bitch.

He isn’t a birder but realized (when a small flock walked through their friggin’ campsite) “hey, I think that’s the bird Sedgley’s always looking for.” Like any good friend, he knew that he could always hang this over my head.

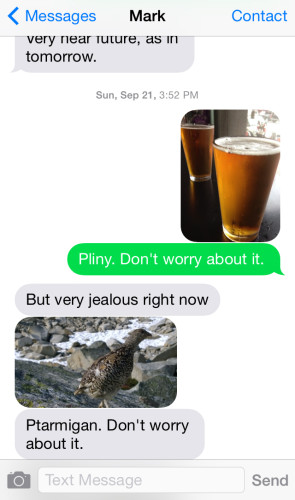

And it’s a card he wasn’t shy about playing. Like when I was down in San Francisco enjoying a pint of his favorite beer, Pliny the Elder (a rare India Pale Ale no longer imported into Washington State). He was jealous, but he knew resending the image of his ptarmigan would be worse.

The situation had escalated from yellow to red. I had to find this bird. And with a move to the Bay Area in our very near future, my window was rapidly closing.

I selected the hike up the Sahale Arm from Cascade Pass—fourteen miles round trip and 3,500 ft of elevation gain. It was a location well-known for ptarmigan, but nothing is guaranteed when you seek a winged creature that is well-camouflaged in both rock and snow.

On October 5th, we set off on what would be our last hike of the year. We left Seattle at 6AM and met our friends Mark (yup, that Mark) and Sheryl, who had camped there the night before, at the trailhead at 9AM. Everyone knew that we were there to find ptarmigan. Mark had already seen ptarmigan – a fact that he often repeated – but was excited to see black bear and eat huckleberries.

We made quick work of the gradual, switchback-littered climb up to Cascade Pass. We only stopped long enough to enjoy the breathtaking scenery—a cliche I don’t use lightly. Tall, granite mountains separated the thin, puffy clouds and a light dusting of snow from the orange and yellow dappled avalanche chutes at their feet. Streams threaded through cracks in the fissured rock face. It was the closest any of us had seen of Middle Earth in our state.

A heavy mist disappeared as quickly as it arrived. A pair of Sooty Grouse made sure that we had at least one chicken-relative on the day’s checklist.

At Cascade Pass, fellow hikers told stories of the large male bear that had been foraging nearby all day yesterday. We scanned the valley. Nothing.

We took a left and headed up the steeper climb to a ridge that overlooked Hearts Lake. Behind stood the imposing Sahale Peak, which held the Sahale Glacier and, hopefully, our avian target. Within minutes, Mark spotted a dark object on a far meadow: his first Black Bear in Washington. Things were looking up.

And then, after we enjoyed a leisurely lunch, as we were on the ridgeline called Sahale Arm – the most exposed section of the trail – the weather turned. The breeze built to a wind and continued to grow, as did the moisture contained within. We hunkered behind a boulder to put on more layers and our rain gear. As we continued up to the ptarmigan habitat, it was clear that the weather wasn’t going to let up (my light hiking pants were already soaked through) and the patience of my crew was wearing thin.

“You got five minutes,” my wife worded strongly enough to be heard over the gusts. With the marital clock ticking, I picked up my pace in hopes to get higher and increase my chances. Scampering up the wet rocks required more concentration.

I couldn’t believe my luck. Why now? Why did the only rain of the day have to occur as soon as we entered good ptarmigan habitat? The ptarmigan gods must have deemed me unworthy, yet again. The hood of my rain jacket was nearly soaked through and sticking to the side of my head. And with the deafening sound of a driving rain against my ear, I recalled all the other failed attempts that had preceded today. This one stung though: it’d likely be years before I could try again.

“Sedgie! They are right here!”

I turned around and saw my wife – about fifty feet behind me – excitedly pointing to a patch of snow just off trail. She isn’t a birder, but no one could mistake anything up here for a ptarmigan.

I almost broke my ankle running back.

Sure enough, there they were: four exquisite White-tailed Ptarmigan in a patch of snow right next to the trail. Blinded by frustration and near-freezing precipitation, I had literally passed within six feet of the near-still birds, who were sporting about 80% of their pure-white winter plumage. Thanks to my wife’s keen eyes and an errant pebble kicked up by her boot, White-tailed Ptarmigan was no longer a nemesis.

With foggy binoculars, I watched as they picked juniper berries from the snows edge, unperturbed by the four onlookers. After a few minutes, the interest of my hiking mates waned – as did the rain – and I had a few blessedly dry minutes to study them more closely. They were even growing the feathered snowshoes they use in winter to increase the surface area of feet—snowshoes for their wintery habitat.

After twenty minutes, the fingers of my ever-patient wife were near numb. It was time to go.

I practically floated over the trail back down to our car. Sure, it was a check on a list. But, as always, it means much, much more.